Steve Milton’s Blog……

I had just moved into a new house in Tottenham. There was a Large Swedish Home Furnishings shop nearby, and I was keen to try out the idea of flat-pack furniture for the first time.

I’d get back with my large box. Unpack it.

Lay out all the bits of wood, screws, plastic plugs and metal thingamyjigs.

Then I’d open the instructions.

That’s when my problems would start. The instructions appeared to have been written in Swedish, then translated into Urdu, then from Urdu into English.

By someone who spoke no Urdu, no Swedish, and certainly no English.

Routinely my best efforts would result in tangled mess of ill-fitting parts that were destined to fall victim to my heartfelt DIY motto:

“If at first you don’t succeed………smash it to bits with a hammer”

In fairness to Large Swedish Home Furnishings Companies – their instructions have improved enormously in recent years. I can honestly say I haven’t smashed any of their stuff to bits with a hammer for, ooh, ages.

I wish more companies would listen to their customers complaints though, and really think about how they explain things.

After all, we are much more likely to buy something or use a service if we understand what it is and how to use it. You’d imagine companies and organisations would be falling over themselves to be clear in their messages.

But no. From bus timetables to self-service checkouts in supermarkets we are bombarded by messages and instructions that seem to be purposely designed to make our day just that little bit harder.

“UNIDENTIFIED ITEM IN BAGGING AREA”!!!

Excuse me?

“UNIDENTIFIED ITEM IN BAGGING AREA”!!!

The merciless torturing of the English language aside, what on earth does it mean, and what I am meant to do about it?

Of course, most of the time we can work out what things mean.

We just damn well shouldn’t have to anywhere near as much as we do.

…..and it’s not just one thing of course – as we go through our day we encounter these little challenges over and over again – each one of which adds another little bit to our ‘cognitive load’. Each makes our day that little bit harder, bit by bit, message by message. They might seem like little things, but together they weigh us down.

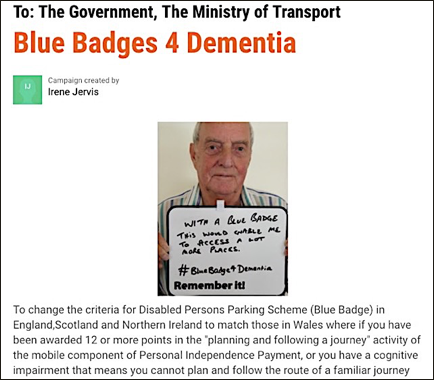

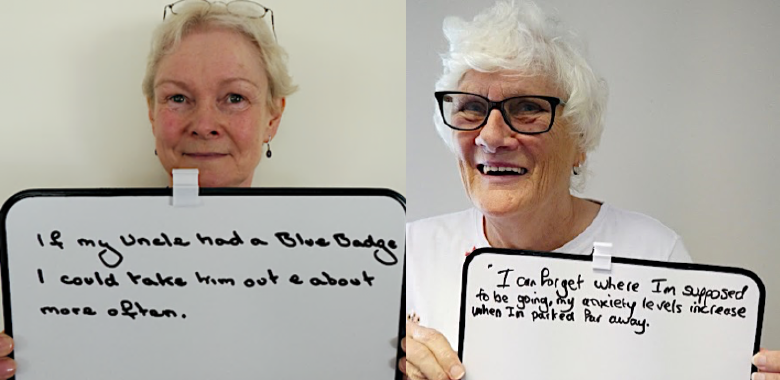

The onset of dementia can make it even harder for people to translate bad information. This can make it harder to people to get out and about, and to do many of the things the rest of us take for granted.

These can be very real barriers for people.

- The badly designed bus timetable that meant someone got on the wrong bus and got lost, or went home having failed to work out what to do next.

- The shrieks of outrage from the self-service checkout, devoid of either meaning or direction that sent the would-be customer scurrying out of shop, mission unaccomplished.

We know what can happen when we begin to struggle, or fail in certain tasks. It means we are less likely to risk failing again, and stay home where it is safe. We disengage.

Many people with dementia have told us that a single incident like this can send them into a tailspin and have a huge impact on their confidence in their ability to interact with the world. They disengage.

How much easier would life be for all of us of if things were just a little bit clearer?

This is why, a few years ago we worked with a small group of people with dementia to write guidelines on writing dementia-friendly information.

Since then we have used them to produce dementia-friendly materials for lots of events and organisations, from conferences to lay summaries of academic papers.

What is very striking though is that not only do people with dementia find these versions easier, so does everyone else.

We first realised this when we produced a dementia friendly timetable for a conference. We had to go across the road to a photocopying shop for more copies as they had all been snaffled up in preference to the main conference timetable.

We can see the impact we can have by making things just a little easier for everyone.

That is why we are working with people with dementia on a new service called Crystal Clear.

Crystal Clear will help organisations to produce information that is easier for everyone to understand.

We have already started to work on some documents for another dementia organisation – and people with dementia are proving hugely insightful into the changes that need to be made.

When we are finished, I want to revisit the guidelines we wrote about dementia friendly information. They were written a few years ago, and things have changed. We’ll be involving the whole DEEP network in a discussion about the challenges that people face in understanding written information – and this will help us to provide better guidance to others.

We believe that people with dementia have unique insights and understanding of how to make the world an easier and better place for everyone.

My dear friend Lynda Hughes once said to me “people with dementia have a wisdom that I don’t see anywhere else. They can save the world”.

Sometimes as the messages from mobile phones, computers, video screens and the Daleks inside self-service checkouts swarm around my head I am reminded how right she was.

Now where’s my hammer?